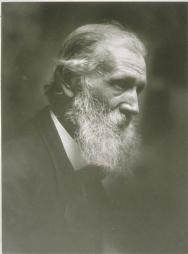

Dear Friends and Colleagues -- On the 165th Anniversary of John Muir's birth in Dunbar, Scotland, on April 21, 1838, I'd like once again to share with you two of his writings about life, nature, and those who would destroy the earth's wild places. Today, as we celebrate Muir's accomplishments, glorification of nature, and wisdom about what needs to be done, we can honor his memory by working for true global security -- environmental security -- against the "selfish seekers of immediate mammon."

Happy birthday, Johnnie!

First, fundamental thoughts about those who would destroy nature:

John

Muir, SAVE THE REDWOODS,

Sierra

Club Bulletin, vol. XI, No. 1 (January, 1920), pp. 1-4.

(Excerpt)

John

Muir, SAVE THE REDWOODS,

Sierra

Club Bulletin, vol. XI, No. 1 (January, 1920), pp. 1-4.

(Excerpt)

(The full text of this wonderful article is available by

clicking on

the title above)

We are often told that

the world is going

from bad to worse,

sacrificing everything to mammon. But this righteous uprising in

defense of God's

trees in the midst of exciting politics and wars is telling a different

story, and every Sequoia, I fancy, has heard the good news and is

waving

its branches for joy. The wrongs done to trees, wrongs of every sort,

are

done in the darkness of ignorance and unbelief, for when light comes

the

heart of the people is always right. Forty-seven years ago one of these

Calaveras King Sequoias was laboriously cut down, that the stump might

be

had for a dancing-floor. Another, one of the finest in the grove, more

than three hundred feet high, was skinned alive to a height of one

hundred

and sixteen feet from the ground and the bark sent to London to show

how

fine and big that Calaveras tree was—as sensible a scheme as

skinning

our

great men would be to prove their greatness. This grand tree is of

course

dead, a ghastly disfigured ruin, but it still stands erect and holds

forth

its majestic arms as if alive and saying, "Forgive them; they know not

what

they do." Now some millmen want to cut all the Calaveras trees into

lumber

and money. But we have found a better use for them. No doubt these

trees

would make good lumber after passing through a sawmill, as George

Washington

after passing through the hands of a French cook would have made good

food. But both for Washington and the tree that bears his name higher

uses have

been found.

Could one of these Sequoia Kings come to

town in all its

godlike

majesty so as to be strikingly seen and allowed to plead its own cause,

there would never again be any lack of defenders.…

And second, the story of Muir's fundamental awakening about the value of nature:

The Calypso Borealis

[Source: The Life and

Letters of John Muir, edited by William Frederic

Badè (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924).]

[Source: The Life and

Letters of John Muir, edited by William Frederic

Badè (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924).]Introduction: In 1864, John Muir was wandering through the swamps of Canada, looking for flowers and trees ("botanising") and working at various odd jobs.* During this time, Muir long sought a rare orchid, the Calypso borealis. The story of his discovery of Calypso was his first published writing, having been sent on to a newspaper by his former College professor, J.D. Butler, to whom he had written of the discovery in a letter. Years later, Muir expanded on the story in the autobiographical fragment below.

* That introduction leaves out the essential fact that Muir was wandering in Canada to avoid the draft for the Civil War. (RAC)

[Stephen Fox, in his book, "John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement," says of this event in Muir's life "Years later he ranked this encounter along with meeting Emerson as the two supreme moments in his life. Aside from the emotional release it allowed him, finding Calypso borealis in that swamp crystallized an attitude, providing the germ of an idea that would eventually dominate his thinking. Hidden away in a thick tangle of trees and bogs, far from the intentions or even the sight of man, those orchids did nothing 'useful.' Yet they reassured Muir in his moment of need without performing any practical task, simply by existing for themselves." (pp. 43-44) -- RAC]

After earning a few dollars working on my brother-in law's farm near Portage [Wisconsin], I set off on the first of my long lonely excursions, botanising in glorious freedom around the Great Lakes and wandering through innumerable tamarac and arbor-vitae swamps, and forests of maple, basswood, ash, elm, balsam, fir, pine, spruce, hemlock, rejoicing in their bound wealth and strength and beauty, climbing the trees, revelling in their flowers and fruit like bees in beds of goldenrods, glorying in the fresh cool beauty and charm of the bog and meadow heathworts, grasses, carices, ferns, mosses, liverworts displayed in boundless profusion.

The rarest and most beautiful of the flowering plants I discovered on this first grand excursion was Calypso borealis (the HIder of the North). I had been fording streams more and more difficult to cross and wading bogs and swamps that seemed more and more extensive and more difficult to force one's way through. Entering one of these great tamarac and arbor-vitae swamps one morning,holding a general though very crooked course by compass, struggling through tangled drooping branches and over and under broad heaps of fallen trees, I began to fear that I would not be able to reach dry ground before dark, and therefore would have to pass the night in the swamp and began, faint and hungry, to plan a nest of branches on one of the largest trees or windfalls like a monkey's nest, or eagle's, or Indian's in the flooded forests of the Orinoco described by Humboldt.

But when the sun was getting low and everything seemed most bewildering and discouraging, I found beautiful Calypso on the mossy bank of a stream, growing not in the ground but on a bed of yellow mosses in which its small white bulb had found a soft nest and from which its one leaf and one flower sprung. The flower was white and made the impression of the utmost simple purity like a snowflower. No other bloom was near it, for the bog a short distance below the surface was still frozen, and the water was ice cold. It seemed the most spiritual of all the flower people I had ever met. I sat down beside it and fairly cried for joy.

It seems wonderful that so frail and lovely a plant has such power over human hearts. This Calypso meeting happened some forty-five years ago, and it was more memorable and impressive than any of my meetings with human beings excepting, perhaps, Emerson and one or two others. When I was leaving the University, Professor J.D. Butler said, "John, I would like to know what becomes o you, and I wish you would write me, say once a year, so I may keep you in sight. " I wrote to the Professor, telling him about this meeting with Calypso, and he sent the letter to an Eastern newspaper [The Boston Recorder] with some comments of his own. These, as far as I know, were the first of my words that appeared in print.

How long I sat beside Calypso I don't know. Hunger and weariness vanished, and only after the sun was low in the west I plashed on through the swamp, strong and exhilarated as if never more to feel any mortal care. At length I saw maple woods on a hill and found a log house. I was gladly received. "Where ha ye come fra? The swamp, that awfu' swamp. What were ye doin' there?" etc. "Mony a puir body has been lost in that muckle, cauld, dreary bog and never been found." When I told her I had entered it in search of plants and had been in it all day, she wondered how plants could draw me to these awful places, and said, "It's god's mercy ye ever got out."

Oftentimes I had to sleep without blankets, and sometimes without supper, but usually I had no great difficulty in finding a loaf of bread here and there at the houses of the farmer settlers in the widely scattered clearings. With one of these large backwoods loaves I was able to wander many a long wild fertile mile in the forests and bogs, free as the winds, gathering plants, and glorying in God's abounding inexhaustible spiritual beauty bread. Storms, thunderclouds, winds in the woods - were welcomed as friends.

Accessed April 21, 2003 at http://www.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/calypso_borealis_by_muir.html