April 21, 2005

For the 167th anniversary of John Muir's birth on April 21, 1838, once again I shared some of Muir's thoughts about how to deal with worldly cares and struggles. I hope they will refresh you and yours, and you will continue to join Muir in "Hoping that we will be able to do something for wildness and make the mountains glad." [Letter to Prof. Henry Senger, May 22, 1892]

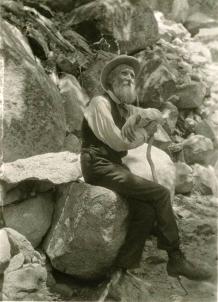

Happy 167th Birthday, Johnnie!

… My life these days is like the life of a glacier, one eternal grind, and the top of my head suffers a weariness at times that you know nothing about. I'm glad to see by the hills across the bay, all yellow and purple with buttercups and gilias, that spring is blending fast into summer, and soon I'll throw down my pen, and take up my heels to go mountaineering once more.

--John

Muir,

Letter to his sister, Sarah Muir Galloway, April 17th, 1876

Can’t you come out and go with me to the mountains next July? You would be my guest and I would be your guide and servant, make your beds, feed you and lead you by the quiet waters of crystal lakes and along the songful rivers of snowy cataracts and fountain glaciers, and in this I would not only obey my heart but in some measure repay you for that wonderful botanical lesson you gave me on the steps of our dormitory, which has never been forgotten and which has influenced all my after life….

--John

Muir,

Letter to Judge Milton S. Griswold, April 3, 1909*

My dear old Friend & Teacher:

I was delighted with your long letter recalling our happy university days. The older we grow the more fondly do we look back to the days of youth and early manhood when all the world lay before us to choose our ways. A first volume of autobiography entitled “My boyhood and Youth”, has just been published by Houghton, Mifflin & Co. of Boston, and as soon as I receive copies I will take great pleasure in sending one to you suitably inscribed. I am sure you will read with lively interest the account I give in full of my first lesson in botany from you while we stood together under an overhanging branch of a locust tree near the steps of the North dormitory. The book is mostly a boy’s book, giving an account of my school days in Scotland and life on a Wisconsin farm, and then going to the University, the book ending with my University studies when I Started off into the wilderness. I am now at work on a book on Alaska and I find that I have so many notes and the subject is so large, it is a very difficult thing to know what to put in and what to leave out and get it all in shape. I spent over a year 1911-12 in South American and South Africa, possibly another year I spent in Russia going from Petersburg to Moscow, thence down to the Crimea and the Black Sea into the Caucasus to Tiflin, and then across the Caucasus to Moscow, thence across the Urals to Siberia and Lake Baikel down the Amoor River and then through Manchuria down to Japan and China, down to Singapore, up into India and the Himalaya, into the Deodar Forest etc. Had fine views of the great snowy mountains Kung junga and others. Went down into Egypt, up the Nile, returned through the Red Sea to Aden, thence down to Australia where I had a fine time studying the eucalyptus forest. Thence over to New Zealand, a wonderful country, thence back to Hong Kong and Japan, and so to San Francisco. Have never written anything on these grand trips, but I may some time if I live long enough. The fact is I never intended to write any books. I have only got out some six so far. Hoping your boys may enjoy the story of my boy days, I am ever

Faithfully

Yours, John

Muir

--John Muir, Letter to Judge Milton S. Griswold, March 27, 1913*

--John Muir, Letter to Judge Milton S. Griswold, March 27, 1913*

When I was a boy in Scotland I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life I've been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures. Fortunately around my native town of Dunbar, by the stormy North Sea, there was no lack of wildness, though most of the land lay in smooth cultivation. With red-blooded playmates, wild as myself, I loved to wander in the fields to hear the birds sing, and along the seashore to gaze and wonder at the shells and seaweeds, eels and crabs in the pools among the rocks when the tide was low; and best of all to watch the waves in awful storms thundering on the black headlands and craggy ruins of the old Dunbar Castle when the sea and the sky, the waves and the clouds, were mingled together as one. We never thought of playing truant, but after I was five or six years old I ran away to the seashore or the fields almost every Saturday, and every day in the school vacations except Sundays, though solemnly warned that I must play at home in the garden and back yard, lest I should learn to think bad thoughts and say bad words. All in vain. In spite of the sure sore punishments that followed like shadows, the natural inherited wildness in our blood ran true on its glorious course as invincible and unstoppable as stars.

--John

Muir, The

Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913) Ch. I. A Boyhood In

Scotland, pp

1-2

One of our best playgrounds was the famous old Dunbar Castle, to which King Edward fled after his defeat at Bannockburn. It was built more than a thousand years ago, and though we knew little of its history, we had heard many mysterious stories of the battles fought about its walls, and firmly believed that every bone we found in the ruins belonged to an ancient warrior. We tried to see who could climb highest on the crumbling peaks and crags, and took chances that no cautious mountaineer would try. That I did not fall and finish my rock-scrambling in those adventurous boyhood days seems now a reasonable wonder.

Among our best games were running, jumping, wrestling, and scrambling. I was so proud of my skill as a climber that when I first heard of hell from a servant girl who loved to tell its horrors and warn us that if we did anything wrong we would be cast into it, I always insisted that I could climb out of it. I imagined it was only a sooty pit with stone walls like those of the castle, and I felt sure there must be chinks and cracks in the masonry for fingers and toes. Anyhow the terrors of the horrible place seldom lasted long beyond the telling; for natural faith casts out fear.

Most of the Scotch children believe in ghosts, and some under peculiar conditions continue to believe in them all through life. Grave ghosts are deemed particularly dangerous, and many of the most credulous will go far out of their way to avoid passing through or near a graveyard in the dark. After being instructed by the servants in the nature, looks and habits of the various black and white ghosts, boowuzzies, and witches we often speculated as to whether they could run fast, and tried to believe that we had a good chance to get away from most of them. To improve our speed and wind, we often took long runs into the country. Tam o' Shanter's mare outran a lot of witches,--at least until she reached a place of safety beyond the keystone of the bridge,--and we thought perhaps we also might be able to outrun them.

--John

Muir, The

Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913) Ch. I. A Boyhood In

Scotland, pp

17-19

The roof of our house, as well as the crags and walls of the old castle, offered fine mountaineering exercise. Our bedroom was lighted by a dormer window. One night I opened it in search of good scootchers and hung myself out over the slates, holding on to the sill, while the wind was making a balloon of my nightgown. I then dared David to try the adventure, and he did. Then I went out again and hung by one hand, and David did the same. Then I hung by one finger, being careful not to slip, and he did that too. Then I stood on the sill and examined the edge of the left wall of the window, crept up the slates along its side by slight finger-holds, got astride of the roof, sat there a few minutes looking at the scenery over the garden wall while the wind was howling and threatening to blow me off, then managed to slip down, catch hold of the sill, and get safely back into the room. But before attempting this scootcher, recognizing its dangerous character, with commendable caution I warned David that in case I should happen to slip I would grip the rain-trough when I was going over the eaves and hang on, and that he must then run fast downstairs and tell father to get a ladder for me, and tell him to be quick because I would soon be tired hanging dangling in the wind by my hands. After my return from this capital scootcher, David, not to be outdone, crawled up to the top of the windowroof, and got bravely astride of it; but in trying to return he lost courage and began to greet (to cry), "I canna get doon. Oh, I canna get doon." I leaned out of the window and shouted encouragingly, "Dinna greet, Davie, dinna greet, I'll help ye doon. If you greet, fayther will hear, and gee us baith an awful' skelping." Then, standing on the sill and holding on by one hand to the window-casing, I directed him to slip his feet down within reach, and, after securing a good hold, I jumped inside and dragged him in by his heels. This finished scootcher-scrambling for the night and frightened us into bed.

--John

Muir, The

Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913) Ch. I. A Boyhood In

Scotland, pp

20-22

I received my first lesson in botany from a student by the name of Griswold, who is now County Judge of the County of Waukesha, Wisconsin. In the University he was often laughed at on account of his anxiety to instruct others, and his frequently saying with fine emphasis, "Imparting instruction is my greatest enjoyment." One memorable day in June, when I was standing on the stone steps of the north dormitory, Mr. Griswold joined me and at once began to teach. He reached up, plucked a flower from an overspreading branch of a locust tree, and, handing it to me, said, "Muir, do you know what family this tree belongs to?"

"No," I said, "I don't know anything about botany."

"Well, no matter," said he, "what is it like?"

"It's like a pea flower," I replied.

"That's right. You're right," he said, "it belongs to the Pea Family."

"But how can that be," I objected, "when the pea is a weak, clinging, straggling herb, and the locust a big, thorny hardwood tree?"

"Yes, that is true," he replied, "as to the difference in size, but it is also true that in all their essential characters they are alike, and therefore they must belong to one and the same family. …

This fine lesson charmed me and sent me flying to the woods and meadows in wild enthusiasm. Like everybody else I was always fond of flowers, attracted by their external beauty and purity. Now my eyes were opened to their inner beauty, all alike revealing glorious traces of the thoughts of God, and leading on and on into the infinite cosmos. I wandered away at every opportunity, making long excursions round the lakes, gathering specimens and keeping them fresh in a bucket in my room to study at night after my regular class tasks were learned; for my eyes never closed on the plant glory I had seen.

--John

Muir, The

Story of My Boyhood and Youth (1913) Ch. VIII. The World

and the

University, pp 280-3

… Nothing can be done well at a speed of forty miles a day. The multitude of mixed, novel impressions rapidly piled on one another make only a dreamy, bewildering, swirling blur, most of which is unrememberable. Far more time should be taken. Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grass and gentians of glacier meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of Nature's darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. As age comes on, one source of enjoyment after another is closed, but Nature's sources never fail. Like a generous host, she offers here brimming cups in endless variety, served in a grand hall, the sky its ceiling, the mountains its walls, decorated with glorious paintings and enlivened with bands of music ever playing. The petty discomforts that beset the awkward guest, the unskilled camper, are quickly forgotten, while all that is precious remains. Fears vanish as soon as one is fairly free in the wilderness.

--John

Muir, Our

National Parks, Chapter II, The Yellowstone National Park,

1901,

page

56.

* Source for the two Griswold letters:

http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cgi-bin/docviewer.exe?CISOROOT=/tp&CISOPTR=8120, Accessed April 19, 2005