Dear friends,

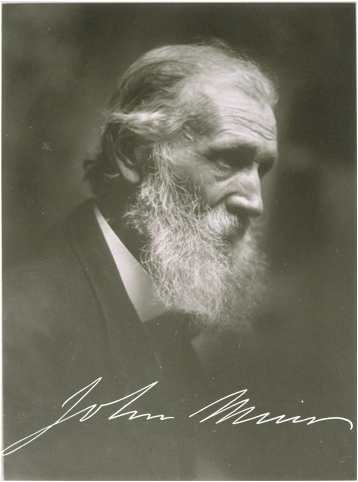

Welcome to the 2020 installment in my series of John Muir birthday

messages, celebrating anniversaries of Muir's birth on April 21, 1838.

On the occasion of Muir’s 182nd birthday – and the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day* on April 22nd – I thought it would be

worthwhile to reflect on

Muir’s public service and advocacy for nature. The excerpt below

is from William Frederic Badè, The Life and Letters of John Muir,

(Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1924), Chapter XVIII:

His Public Service.**

Intimately

as his name was already identified with the natural beauty

of California in 1879, the service which Muir was ultimately to render

to the nation was only beginning at that time. Then there was only one

national park, that of the Yellowstone, and no national forest reserves

at all. Amid such a wealth of beautiful forests and wildernesses as our

nation then possessed it required a very uncommon lover of nature and

of humanity to advocate provision against a day of need. But that

friend of generations unborn arose in the person of John Muir. Before

he or any one had ever heard of national parks the idea of preserving

some sections of our natural flora in their unspoiled wildness arose

spontaneously in his mind,

Intimately

as his name was already identified with the natural beauty

of California in 1879, the service which Muir was ultimately to render

to the nation was only beginning at that time. Then there was only one

national park, that of the Yellowstone, and no national forest reserves

at all. Amid such a wealth of beautiful forests and wildernesses as our

nation then possessed it required a very uncommon lover of nature and

of humanity to advocate provision against a day of need. But that

friend of generations unborn arose in the person of John Muir. Before

he or any one had ever heard of national parks the idea of preserving

some sections of our natural flora in their unspoiled wildness arose

spontaneously in his mind, It was a lovely carex meadow beside Fountain Lake, on his father's first Wisconsin farm, that gave him the germinal idea, of a park in which plant societies were to be protected in their natural state. During the middle sixties, as he was about to leave his boyhood home forever, he found unbearable the thought of leaving this precious meadow unprotected, and offered to purchase it from his brother-in-law on condition that cattle and hogs be kept securely fenced out. Early correspondence shows that he pressed the matter repeatedly, but his relative treated the request as a sentimental dream, and ultimately the meadow was trampled out of existence. More than thirty years later, at a notable meeting of the Sierra Club in 1895, he for the first time made public this natural park dream of his boyhood. It was the national park idea in miniature, and the proposal was made before even the Yellowstone National Park had been established.

This was the type of man who during the decade between 1879 and 1889 wrote for "Scribner's Monthly" and the "Century Magazine" a series of articles the like of which had never been written on American forests and scenery. Such were Muir's articles entitled "In the Heart of the California Alps," "Wild Sheep of the Sierra," "Coniferous Forests of the Sierra Nevada," and "Bee-Pastures of California." There was also the volume, edited by him, entitled "Picturesque California," with numerous articles by himself. The remarkably large correspondence which came to him as a result of this literary activity shows how deep was its educative effect upon the public mind.

Then came the eventful summer of 1889, during which he took Robert Underwood Johnson, one of the editors of the "Century," camping about Yosemite and on the Tuolumne Meadows, where, as Muir says, he showed him how uncountable sheep had eaten and trampled out of existence the wonderful flower gardens of the seventies. We have elsewhere shown how the two then and there determined to make a move for the establishment of what is now the Yosemite National Park, and to make its area sufficiently comprehensive to include all the headwaters of the Merced and the Tuolumne. This was during President Harrison's administration, and, fortunately for the project, John W. Noble, a faithful and far-sighted servant of the American people, was then Secretary of the Interior.

One may imagine with what fervor Muir threw himself into that campaign. The series of articles on the Yosemite region which he now wrote for the "Century" are among the best things he has ever done. Public-spirited men all over the country rallied to the support of the National Park movement, and on the first of October, 1890, the Yosemite National Park bill went through Congress, though bitterly contested by all kinds of selfishness and pettifoggery. A troop of cavalry immediately came to guard the new park; the "hoofed locusts" were expelled, and the flowers and undergrowth gradually returned to the meadows and forests.

The following year (1891) Congress passed an act empowering the President to create forest reserves. This was the initial step toward a rational forest conservation policy, and President Harrison was the first to establish forest reserves--to the extent of somewhat more than thirteen million acres. We cannot stop to go into the opening phases of this new movement, but the measure in which the country is indebted to John Muir also for this public benefit may be gathered from letters of introduction to scientists abroad which influential friends gave to Muir in 1893 when he was contemplating extensive travels in Europe. "It gives me great pleasure," wrote one of them, "to introduce to you Mr. John Muir, whose successful struggle for the reservation of about one-half of the western side of the Sierra Nevada has made him so well known to the friends of the forest in this country."

During his struggle for the forest reservations and for the establishment of the Yosemite National Park Muir had the effective cooperation of a considerable body of public-spirited citizens of California, who in 1892 were organized into the Sierra Club, in part, at least, for the purpose of assisting in creating public sentiment and in making it effective. During its long and distinguished public service this organization never swerved from one of its main purposes, to enlist the support and cooperation of the people and the government in preserving the forests and other features of the Sierra Nevada Mountains," and when that thrilling volume of Muir's, "My First Summer in the Sierra," appeared in 1911, it was found to be dedicated " To the Sierra Club of California, Faithful Defender of the People's Playgrounds."

*

Personal Recollection: One of the earliest – and certainly one of

largest -- celebration of Earth Day took place in March, 1970 at the Enact

Environmental Teach-in at The University of Michigan in Ann

Arbor. It was in March because UM’s finals week schedule included April

22nd. Former Sierra Club Conservation Director, Doug Scott, then

a UM graduate student in the School of Natural Resources, was a

co-chair of the celebration. Former Club President, then an

Assistant Professor of Botany, Richard Cellarius was an informal

faculty advisor. Both Dave Brower and Mike McCloskey participated in

the events, as did Arthur Godfrey, Barry Commoner, and Senators Phil

Hart and Edmund Muskie. The Chicago cast of Hair performed before

14,000 people in the University’s Crisler basketball arena in the

kick-off event. The Ann Arbor Ecology Center, established during the

Teach-in with the leadership involvement of faculty wife, Doris

Cellarius, is still going strong. It was an exciting time, and it is

wonderful that Earth Day is still on the calendar after 50 years – and,

unfortunately, it is still needed. 😖

*

Personal Recollection: One of the earliest – and certainly one of

largest -- celebration of Earth Day took place in March, 1970 at the Enact

Environmental Teach-in at The University of Michigan in Ann

Arbor. It was in March because UM’s finals week schedule included April

22nd. Former Sierra Club Conservation Director, Doug Scott, then

a UM graduate student in the School of Natural Resources, was a

co-chair of the celebration. Former Club President, then an

Assistant Professor of Botany, Richard Cellarius was an informal

faculty advisor. Both Dave Brower and Mike McCloskey participated in

the events, as did Arthur Godfrey, Barry Commoner, and Senators Phil

Hart and Edmund Muskie. The Chicago cast of Hair performed before

14,000 people in the University’s Crisler basketball arena in the

kick-off event. The Ann Arbor Ecology Center, established during the

Teach-in with the leadership involvement of faculty wife, Doris

Cellarius, is still going strong. It was an exciting time, and it is

wonderful that Earth Day is still on the calendar after 50 years – and,

unfortunately, it is still needed. 😖

** Available at https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/life/life_and_letters/chapter_18.aspx.