Dear friends,

Welcome to the 2021 installment in my series of John Muir (1838-1914) birthday messages, celebrating anniversaries of Muir's birth on April 21, 1838. On the occasion of Muir’s 183rd birthday, as a release from the current malaise and pandemic, and in the spirit of fun and amazement, I thought I would share some of Muir's descriptions of his early inventions while still a youth and university student in Wisconsin. [See the Bibliographic Note]

Portland, Oregon

April 21, 2021

One evening when I was reading Church history father was particularly irritable, and called out with hope-killing emphasis, "John, go to bed! Must I give you a separate order every night to get you to go to bed? Now, I will have no irregularity in the family; you must go when the rest go, and without my having to tell you." Then, as an afterthought, as if judging that his words and tone of voice were too severe for so pardonable an offense as reading a religious book, he unwarily added: "If you will read, get up in the morning and read. You may get up in the morning as early as you like."

That night I went to bed wishing with all my heart and soul that somebody or something might call me out of sleep to avail myself of this wonderful indulgence; and next morning to my joyful surprise I awoke before father called me. A boy sleeps soundly after working all day in the snowy woods, but that frosty morning I sprang out of bed as if called by a trumpet blast, rushed downstairs, scarce feeling my chilblains, enormously eager to see how much time I had won; and when I held up my candle to a little clock that stood on a bracket in the kitchen I found that it was only one o'clock. I had gained five hours, almost half a day! "Five hours to myself!" I said, "five huge, solid hours!" I can hardly think of any other event in my life, any discovery I ever made that gave birth to joy so transportingly glorious as the possession of these five frosty hours.

In the

glad, tumultuous excitement of so much suddenly acquired time-wealth,

I hardly knew what to do with

it. I first thought of going on with my

reading,

but the zero weather would make a fire necessary, and it occurred to me

that father might object to the cost of fire-wood that took time to

chop.

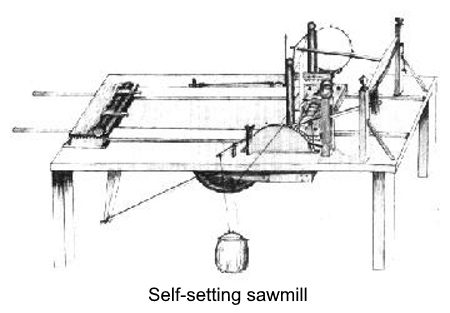

Therefore, I prudently decided to go down cellar, and begin work on a

model

of a self-setting sawmill I had invented. Next morning I managed to get

up at the same gloriously early hour, and though

the temperature of the

cellar was a little below the freezing point, and my light was only a

tallow

candle, the mill work went joyfully on. There were a few tools in a

corner

of the cellar--a vise, files, a hammer, chisels, etc., that father had

brought

from Scotland, but no saw excepting a coarse crooked one that wsa unfit

for sawing dry hickory or oak. So I made a fine-tooth saw suitable for

my work out of a strip of steel that had formed part of an

old-fashioned

corset, that cut the hardest wood smoothly. I

also made my own

bradawls,

punches, and a pair of compasses, out of wire and old files.

In the

glad, tumultuous excitement of so much suddenly acquired time-wealth,

I hardly knew what to do with

it. I first thought of going on with my

reading,

but the zero weather would make a fire necessary, and it occurred to me

that father might object to the cost of fire-wood that took time to

chop.

Therefore, I prudently decided to go down cellar, and begin work on a

model

of a self-setting sawmill I had invented. Next morning I managed to get

up at the same gloriously early hour, and though

the temperature of the

cellar was a little below the freezing point, and my light was only a

tallow

candle, the mill work went joyfully on. There were a few tools in a

corner

of the cellar--a vise, files, a hammer, chisels, etc., that father had

brought

from Scotland, but no saw excepting a coarse crooked one that wsa unfit

for sawing dry hickory or oak. So I made a fine-tooth saw suitable for

my work out of a strip of steel that had formed part of an

old-fashioned

corset, that cut the hardest wood smoothly. I

also made my own

bradawls,

punches, and a pair of compasses, out of wire and old files.

After completing my self-setting sawmill I dammed one of the streams in the meadow and put the mill in operation. This invention was speedily followed by a lot of others--water-wheels, curious doorlocks and latches, thermometers, hygrometers, pyrometers, clocks, a barometer, an automatic contrivance for feeding the horses at any required hour, a lamp-lighter and fire-lighter, an early-or-late-rising machine, and so forth.

After the sawmill was proved and discharged from my mind, I happened to think it would be a fine thing to make a timekeeper which would tell the day of the week and the day of the month, as well as strike like a common clock and point out the hours; also to have an attachment whereby it could be connected with a bedstead to set me on my feet at any hour in the morning; also to start fires, light lamps, etc. I had learned the time laws of the pendulum from a book, but with this exception I knew nothing of timekeepers, for I had never seen the inside of any sort of clock or watch. After long brooding, the novel clock was at length completed in my mind, and was tried and found to be durable and to work well and look well before I had begun to build it in wood. I carried small parts of it in my pocket to whittle at when I was out at work on the farm using every spare or stolen moment within reach without father's knowing anything about it. In the middle of summer, when harvesting was in progress, the novel time-machine was nearly completed. It was hidden upstairs in a spare bedroom where some tools were kept. I did the making and mending on the farm, but one day at noon, when I happened to be away, father went upstairs for a hammer or something and discovered the mysterious machine back of the bedstead. My sister Margaret saw him on his knees examining it, and at the first opportunity whispered in my ear, "John, fayther saw that thing you're making upstairs." None of the family knew what I was doing, but they knew very well that all such work was frowned on by father, and kindly warned me of any danger that threatened my plans. The fine invention seemed doomed to destruction before its time-ticking commenced, though I thought it handsome, had so long carried it in my mind, and like the nest of Burns's wee mousie it had cost me mony a weary whittling nibble. When we were at dinner several days after the sad discovery, father began to clear his throat to speak, and I feared the doom of martyrdom was about to be pronounced on my grand clock.

"John," he inquired, "what is that thing you are making upstairs?"

I replied in desperation that I didn't know what to call it.

"What! You mean to say you don't know what you are trying to do?"

"Oh, yes," I said, "I know very well what I am doing."

"What, then, is the thing for?"

"It's for a lot of things," I replied, "but getting; people up early in the morning is one of the main things it is intended for; therefore it might perhaps be called an early-rising machine."

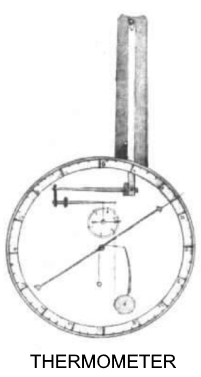

One of my

inventions was a large thermometer made of an iron rod, about

three feet long and five eighths of an inch in diameter, that had

formed

part of a wagon-box. The expansion and contraction of this rod was

multiplied

by a series of levers made of strips of hoop iron. The pressure of the

rod against the levers was kept constant by a small counterweight, so

that

the slightest change in the length of the rod was instantly shown on a

dial about three feet wide multiplied about thirty-two thousand times.

The zero-point was gained by packing the rod in wet snow. The scale was

so large that the big black hand on the white-painted dial could be

seen

distinctly and the temperature read while we were ploughing in the

field

below the house. The extremes of heat and cold caused the hand to make

several revolutions. The number of these revolutions

was indicated on a small dial marked on the larger one. This

thermometer

was fastened on the side of the house, and was so sensitive that when

any

one approached it within four or five feet the heat radiated from the

observer's

body caused the hand of the dial to move so fast that the motion was

plainly

visible, and when he stepped back, the hand moved slowly back to its

normal

position. It was regarded as a great wonder by the neighbors and even

by

my own all-Bible father.

One of my

inventions was a large thermometer made of an iron rod, about

three feet long and five eighths of an inch in diameter, that had

formed

part of a wagon-box. The expansion and contraction of this rod was

multiplied

by a series of levers made of strips of hoop iron. The pressure of the

rod against the levers was kept constant by a small counterweight, so

that

the slightest change in the length of the rod was instantly shown on a

dial about three feet wide multiplied about thirty-two thousand times.

The zero-point was gained by packing the rod in wet snow. The scale was

so large that the big black hand on the white-painted dial could be

seen

distinctly and the temperature read while we were ploughing in the

field

below the house. The extremes of heat and cold caused the hand to make

several revolutions. The number of these revolutions

was indicated on a small dial marked on the larger one. This

thermometer

was fastened on the side of the house, and was so sensitive that when

any

one approached it within four or five feet the heat radiated from the

observer's

body caused the hand of the dial to move so fast that the motion was

plainly

visible, and when he stepped back, the hand moved slowly back to its

normal

position. It was regarded as a great wonder by the neighbors and even

by

my own all-Bible father. The winter was very cold, and I had to go to the schoolhouse and start the fire about eight o'clock to warm it before the arrival of the scholars. This was a rather trying job, and one that my clock might easily be made to do. Therefore, after supper one evening I told the head of the family with whom I was boarding that if he would give me a candle I would go back to the schoolhouse and make arrangements for lighting the fire at eight o'clock, without my having to be present until time to open the school at nine. He said, "Oh, young man, you have some curious things in the school-room, but I don't think you can do that." I said, "Oh, yes! It's easy," and in hardly more than an hour the simple job was completed. I had only to place a teaspoonful of powdered chlorate of potash and sugar on the stove-hearth near a few shavings and kindling, and at the required time make the clock, through a simple arrangement, touch the inflammable mixture with a drop of sulphuric acid. Every evening after school was dismissed, I shoveled out what was left of the fire into the snow, put in a little kindling, filled up the big box stove with heavy oak wood, placed the lighting arrangement on the hearth, and set the clock to drop the acid at the hour of eight; all this requiring only a few minutes.

The first morning after I had made this simple arrangement I invited the doubting farmer to watch the old squat schoolhouse from a window that overlooked it, to see if a good smoke did not rise from the stovepipe. Sure enough, on the minute, he saw a tall column curling gracefully up through the frosty air, but instead of congratulating me on my success he solemnly shook his head and said in a hollow, lugubrious voice, "Young man, you will be setting fire to the schoolhouse." All winter long that faithful clock fire never failed, and by the time I got to the schoolhouse the stove was usually red-hot.

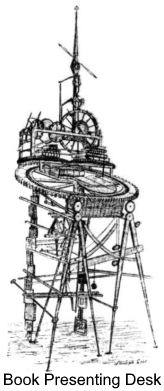

Nevertheless,

I still indulged my love of mechanical inventions. I invented

a desk in which the books I had to study were arranged in order at the

beginning of each term. I also made a bed which set me on my feet every

morning at the hour determined on, and in dark winter mornings just

as the bed set me on the floor it lighted a lamp. Then, after the

minutes

allowed for dressing had elapsed, a click was heard and the first book

to be studied was pushed up from a rack below the top of the desk,

thrown

open, and allowed to remain there the number of minutes required. Then

the machinery closed the book and allowed it to drop back into its

stall,

then moved the rack forward and threw up the next in order, and so on,

all the day being divided according to the times of recitation, and

time

required and allotted to each study. Besides this, I thought it would

be

a fine thing in the summertime when the sun rose early, to dispense

with

the clock-controlled bed machinery, and make use of sunbeams instead.

This

I did simply by taking a lens out of my small spy-glass, fixing it on a

frame on the sill of my bedroom window and pointing it to the sunrise;

the sunbeams focused on a thread burned it through, allowing the bed

machinery

to put me on my feet. When I wished to arise at any given time after

sunrise,

I had only to turn the pivoted frame that held the lens the requisite

number

of degrees or minutes. Thus I took Emerson's advice and hitched my

dumping-wagon

bed to a star.

Nevertheless,

I still indulged my love of mechanical inventions. I invented

a desk in which the books I had to study were arranged in order at the

beginning of each term. I also made a bed which set me on my feet every

morning at the hour determined on, and in dark winter mornings just

as the bed set me on the floor it lighted a lamp. Then, after the

minutes

allowed for dressing had elapsed, a click was heard and the first book

to be studied was pushed up from a rack below the top of the desk,

thrown

open, and allowed to remain there the number of minutes required. Then

the machinery closed the book and allowed it to drop back into its

stall,

then moved the rack forward and threw up the next in order, and so on,

all the day being divided according to the times of recitation, and

time

required and allotted to each study. Besides this, I thought it would

be

a fine thing in the summertime when the sun rose early, to dispense

with

the clock-controlled bed machinery, and make use of sunbeams instead.

This

I did simply by taking a lens out of my small spy-glass, fixing it on a

frame on the sill of my bedroom window and pointing it to the sunrise;

the sunbeams focused on a thread burned it through, allowing the bed

machinery

to put me on my feet. When I wished to arise at any given time after

sunrise,

I had only to turn the pivoted frame that held the lens the requisite

number

of degrees or minutes. Thus I took Emerson's advice and hitched my

dumping-wagon

bed to a star.NOTE: I also believe Muir helped invent grassroots lobbying. Here are a two bits of evidence for that:

TO: Robert Underwood Johnson, Oct 27, 1913 [Letter in Bancroft Library]

Dear Johnson: That letter of yours in Colliers of Oct. 25 is capital, the best ever! We held a Sierra Club meeting last Saturday-‑passed resolutuions and fanned each other to a fierce white Hetch Hetchy heat.

I particularly urged that we must get everybody to write to Senators and the president keeping letters flying all next month thick as storm snow flakes, loaded with park pictures, short circulars, etc. Stir up all other park and playground clubs, women's clubs, etc. ...

Yours bravely ...

John Muir

Damming Hetch Hetchy (From Muir's unpublished journals, circa 1913.)

A great political miracle this of "improving" the beauty of the most beautiful of all mountain parks by cutting down its groves, and burying all the thicket of azalea and wild rose, lily gardens, and ferneries two or three hundred feet deep. After this is done we are promised a road blasted on the slope of the north wall, where nature-lovers may sit on rustic stools, or rocks, like frogs on logs, to admire the sham dam lake, the grave of Hetch Hetchy. This Yosemite Park fight began a dozen years ago. Never for a moment have I believed that the American people would fail to defend it for the welfare of themselves and all the world. The people are now aroused. Tidings from far and near show that almost every good man and woman is with us. Therefore be of good cheer, watch, and pray and fight!

Bibliographic Note:

John Muir, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913. Also available at https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/the_story_of_my_boyhood_and_youth/chapter_7.aspx ff