Welcome to the 2011 message in my series of John Muir birthday messages, celebrating anniversaries of Muir's birth on April 21, 1838. On his 173rd birthday, I depart from my usual custom of sending a Muir quotation, but instead share a perspective from William Keith, a Scotland-born American painter, who frequently accompanied Muir in his ramblings in Yosemite.

Richard Cellarius

Prescott, AZ

April 21, 2011

Historical Notes:

Muir

and Keith met in October 1872 in

Yosemite Valley.

Keith carried a

letter of introduction from a mutual friend, Jeanne Carr. Floy

Hutchings led Keith and two other painters to Muir who was at his cabin

below the Royal Arches. Keith inquired whether Muir knew of any views

that would make a picture. Muir replied that he did, and two days later

led the a group of five (Muir, Keith, Irwin Benoni, Thomas Ross, and

Merrill Moores) to the upper Tuolumne River area [see below*]. As it turned out,

Willie and Johnnie, as they soon called each other, were born in the

same year in Scotland. They became close friends for the next forty

years, until Keith's death in 1911. Keith wrote in his journal that

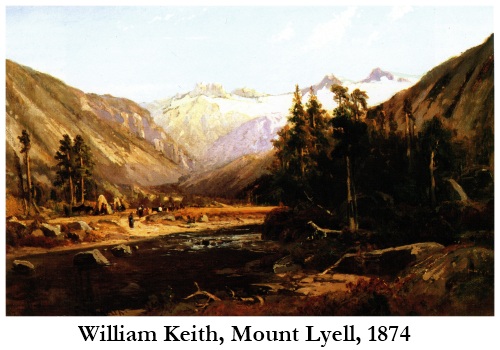

"When we got to Mount Lyell, it was the grandest thing I ever saw. It

was late in October, and at an elevation of 10,000 fttet. The frost had

changed the grasses and a kind of willow to the most brilliant yellows

and reds; these contrasting with the two-leafed pine and Williamson

spruce, the cold gray rocks, the colder snow, made a glorious sight."

Muir reported the outing rather differently, writing that when they

rounded a corner and Mt. Lyell came into view, "Keith dashed forward,

shouting and gesticulating and waving his arms like a madman." Keith,

an epicure, also wrote that Muir was a poor provider on their outings,

and that he tired of bread, dried meat, and sugarless coffee.

Muir

and Keith met in October 1872 in

Yosemite Valley.

Keith carried a

letter of introduction from a mutual friend, Jeanne Carr. Floy

Hutchings led Keith and two other painters to Muir who was at his cabin

below the Royal Arches. Keith inquired whether Muir knew of any views

that would make a picture. Muir replied that he did, and two days later

led the a group of five (Muir, Keith, Irwin Benoni, Thomas Ross, and

Merrill Moores) to the upper Tuolumne River area [see below*]. As it turned out,

Willie and Johnnie, as they soon called each other, were born in the

same year in Scotland. They became close friends for the next forty

years, until Keith's death in 1911. Keith wrote in his journal that

"When we got to Mount Lyell, it was the grandest thing I ever saw. It

was late in October, and at an elevation of 10,000 fttet. The frost had

changed the grasses and a kind of willow to the most brilliant yellows

and reds; these contrasting with the two-leafed pine and Williamson

spruce, the cold gray rocks, the colder snow, made a glorious sight."

Muir reported the outing rather differently, writing that when they

rounded a corner and Mt. Lyell came into view, "Keith dashed forward,

shouting and gesticulating and waving his arms like a madman." Keith,

an epicure, also wrote that Muir was a poor provider on their outings,

and that he tired of bread, dried meat, and sugarless coffee.

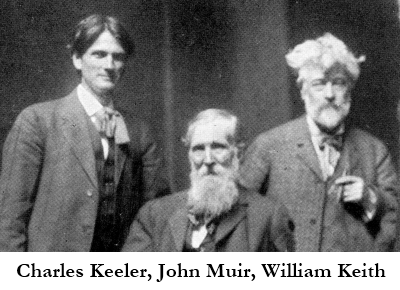

From William Keith, A

friend of John Muir by Steve Pauly http://www.johnmuirassociation.org/archives/archives_1996-february.php

My earliest recollections of John

Muir date

back some

twenty-odd years, to those golden days in William Keith's rather stingy

but glorious studio on Montgomery Street, when Muir would drop in from

his Martinez retreat for a chat with his old painter friend. The two

Scotchmen, who had camped together in Sierra wilds in summer outings,

and cracked jokes at one another's expense in the studio or at one of

the little French restaurants where they lunched during winter visits,

were big elemental natures, both of them. The child-heart each had

treasured in his own peculiar way. they were Willie and Johnnie in

their bantering sallies.

My earliest recollections of John

Muir date

back some

twenty-odd years, to those golden days in William Keith's rather stingy

but glorious studio on Montgomery Street, when Muir would drop in from

his Martinez retreat for a chat with his old painter friend. The two

Scotchmen, who had camped together in Sierra wilds in summer outings,

and cracked jokes at one another's expense in the studio or at one of

the little French restaurants where they lunched during winter visits,

were big elemental natures, both of them. The child-heart each had

treasured in his own peculiar way. they were Willie and Johnnie in

their bantering sallies.

Both were deeply religious natures, but emancipated from formalism and tradition. Both were students and lovers of nature, but where Keith saw color and atmosphere, poetry and romance, in mountain and vale, tree and sky, Muir's eyes were fixed on the ever-changing processes of immutable law.

Those who knew Keith's work best realized that it fell into two groups - a comparatively hard, literal portrayal of the facts of landscape, and a free, impassioned outburst of impressionistic depicting of nature's moods. In his own heart he scorned the former and frankly gloried in the latter. His naturalistic sketches in color were either studies of underlying fact or potboilers for the uninitiated who were not up to his dream rhapsodies.

Muir was at heart a seer. But for him the wonder and glory of nature lay not in its romance of atmosphere and its appeal to human emotions. He saw in it rather the embodiment of divine law, and in a picture looked for a naturalistic portrayal rather than an impressionistic interpretation. So it was that he failed to appreciate his artist friend's finest work. With his dry Scotch humor he loved to twit him in good-natured raillery. Both in the old Montgomery Street studio, and later in the larger Pine Street rooms, I have spent many a happy hour with these two great souls, looking at the pictures and listening to Muir's talk.

As his keen gray eye ranged over the pictures stacked in piles all over the place, he would fall upon a big careful objective study of a Sierra landscape.

"Now there's a real picture, Willie," he would exclaim. "Why don't you paint more like that ?" With a look of defiance the big shaggy-haired painter would draw from the stack a mystical dream of live-oaks, with a green and gold sunset sky, and stand it up on an easel with an impatient wave of his hand.

"What are you trying to make of that? You've stood it upside down, haven't you?" Muir would sally with a mischievous twinkle.

And Keith would finally give it up with:

"There's no use trying to show you pictures, Johnnie."

But in spite of these little pleasantries, which revealed a

fundamentally different approach to nature, the two men had a life-long

admiration and friendship for one another.

From Charles Keeler,

Recollections of John

Muir, Sierra

Club Bulletin, John Muir Memorial Number, (January, 1916),

http://www.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/life/scb_jm_memorial_1916.html.

Keith’s love of nature was one of several

bonds between

him and the great naturalist John Muir, whose friendship was pivotal to

the artist’s career. They shared a transcendent view of

nature, reveling in its beauty, majesty and mystery.

They camped together in the Sierra Nevada range and

the Northwest saw each other when Muir was in the San Francisco area,

and helped inspire each other's work. Muir directly

influenced many of Keith's early Yosemite scenes, encouraged him to

reproduce the precise landscape details, and guided him through some of

the West’s most beautiful vistas.

From William Keith:

Mountains of Shadow and Light,

http://www.stmarys-ca.edu/arts/hearst-art-gallery/exhibits/keith-room/index.html

In 1889, Muir, LeConte and Keith began meeting regularly in William Keith's San Francisco painting studio to discuss the formation of an alpine club to protect and preserve their beloved mountains. With the help of attorney Warren Olney and others, they founded the Sierra Club in May of 1892. http://www.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/press_releases/2_great_grandsons.aspx

*SKETCHING

WITH WILLIAM KEITH[1]

The Great Artist in the Role of an Explorer[2]

It is not generally known that Mr. Keith, the eminent landscape painter, can wield the pen as gracefully and almost with as much power as he does the brush. The following article by Mr. Keith was published in the Boston Advertiser in 1874, and is highly interesting as depicting the resolution of the early-day artists in California to explore this new land and transfer its beauty to canvas.

Eastern artists who read this will see that sketching here on the Pacific slope is a very different thing from sketching in New England. Traveling about in the Sierras, one has to undergo a good deal of hardship and keep it to one's self. Yellow saleratus biscuit, pork and "garden sauce"—otherwise potatoes, make the chief of one's diet in this land of fruits,— I mean when in the mountains. When it was getting on into the fall [of 1872] I set out for the Yosemite and from there went two days further up into the Sierras with John Muir—one of those remarkable men one often meets in California—a very good writer and a scientist. We were gone twelve days from the Yosemite; lived on tea and flour and water; I sickened of the pork. In such places one has to get along with the least possible weight. You are on horseback and can't carry much. It is a matter of scramble, tumble, rumble, and wallow, over moraine, rock, chaparral, rock polished by glaciers so that it glitters and shines in the sun,—chaparral so thick that when you get into it your only way of getting out is to get into a rage and tear things. When we got to Mount Lyell it was the grandest thing I ever saw. It was late in October, and at an elevation of 10,000 feet. The frost had changed the grasses and a kind of willow to the most brilliant yellows and reds; these contrasting with the two-leafed pine and Williamson spruce (the only other kinds of trees growing at that elevation), the cold gray rocks, the colder snow, made a glorious sight.

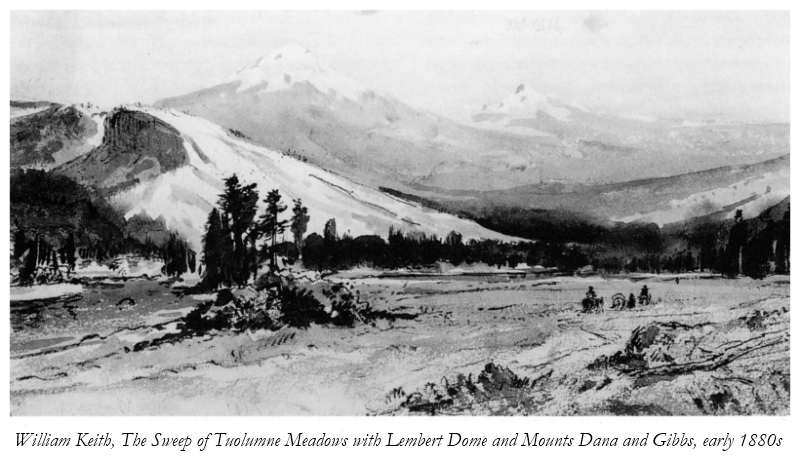

The hardest trip of all was last Summer, when I started up into the Yosemite with the intention of going into the Tuolumne Canyon, a place which only two men had ever been in, and which had been pronounced inaccessible by parties who ought to know. We left the valley with horses and two mules packed with provisions. On the second day after leaving the valley we reached the Divide and camped. After supper I took a stroll along the backbone of the ridge and looked down into the Hetch Hetchy Valley, looked plumb down one mile. The sun was setting, and a golden haze concealed and half revealed a glorious sight. You felt as if you had no resting place, but floated on space. And looking the reverse way,—away for miles and miles,—the summits, in the clear higher air, looked like a company of angels with their lofty heads tipped with the sun's last rays in a flush of glory; patches of snow rose-colored, patches of pine and chaparral, dashes of purple and blue and gold, and over it all the silence of eternity—inexpressible things. And then the gray of twilight. You scramble and jump over huge rocks, dash through chaparral, and so back to camp, head and heart full. Our camp was under the lee of a clump of Williamson spruce, with snow-banks to the right and left of us; remember, we were on the summit. Sitting round the camp-fire, digesting our bacon and flapjacks, and listening to the tales of our guide, we passed the hours until bed time. With blankets rolled around us and a stone for a pillow we slept.

The next morning we sent all the horses back to Yosemite together with the packer, and told him to be there in twelve days from that time. We then made mules of ourselves. My pack was so heavy that I couldn't lift it to my back, but had to get one of my companions to do it for me. We started over snow (this was about seven o'clock A.M.). Blinded by the glare we crept along, resting frequently. We traveled along and got at last into a side canyon, skirting by the way two or three lakes right on the sides of the canyon. Now crossing by jumps the stream which descended from the lakes and melting snow on the summit, now climbing over glacier-polished rock, zigzagging to get down the plumb mile; sometimes we had to take shoes and stockings off and cling to the polished rock for dear life, sometimes following a seam on the side of the rock, not bigger than the hand, carefully placing hands and feet—for the slipping of a couple of inches and you go five or six hundred feet down into a swollen, white-surfaced stream, wider than Washington Street—halting every now and then when we got to a place where stopping would be practicable. About noon we stopped by the side of some chaparral and lunched, tired out. My pack was lead and weighed tons. I derived much satisfaction when stopping, in dragging it behind the bushes, and having a war-dance over it. I kicked and stamped on that pack until I wore my tiredness and exasperation away. You see it didn't hurt the pack, and it helped me.

Our meal over, we started again, and scrambled and pushed and jumped down a few more hundred feet. We got to one place where on the right we saw a river of foam leap over a snow avalanche and a perpendicular wall. On close examination we saw that to get on the avalanche and so ford the river would be dangerous, for the river had worn the snow so that in places we could see that the snow and ice were very thin. We crept down between the snow avalanche and the rock wall, and tunneled our way down still farther, until we found a place to get up on the bank overlooking the stream; and so traveling in such ways we got to the bottom of the canyon about nine o'clock that night. We would have camped before this, but could not find a place sufficiently level for us to sleep on. We made a fire and got supper, too tired to eat, and went to our blankets too tired to sleep. The next morning we left some provisions, a pair of blankets with some dried meat wrapped in them and after a breakfast of sugarless coffee (we forgot sugar), and some of the debris of last night's supper, we looked around and found ourselves in the midst of tangled willows and a kind of stunted birch. We made for the river, hidden from our sight by the thickly growing trees and brush. A dozen or two yards and we stood on the bank of the Tuolumne, the first white party that had ever explored the Tuolumne Canyon.

More About the Great Artist's Mountain Climbing[3]

In an interesting article published in The Wasp recently Mr. Keith described graphically his adventures as one of the first party of explorers who ventured into the Tuolumne Canyon over thirty years ago. In the present article Mr. Keith tells how he retraced his steps from the Tuolumne and got back to their starting point in the Yosemite Valley. The old time painters like Keith did not mind a rough experience of that kind as long as it gave them a new insight of Nature in some new mood.

From the fast-melting snow, finding it impossible to get through the tangled masses onto the banks, we struggled our way up toward the mass of rock to the right, where we jumped from rock to rock clear of chaparral, and at about noon we camped in a beautiful grove of pine, oaks and azaleas. The air was heavy with the fragrance of the azalea. After eating we undertook to fell a tree with a small hatchet, the only weapon of offense or defense in the party. It took about four hours' steady chopping, two that evening and two the next morning, when the tree fell, and in falling the crown broke, and the steady strain of the river carried it down. Muir and I started ahead to see if there was any better place to ford, and after walking an hour or so we came upon a beautiful waterfall—or rather four, one leaping and tumbling after the other. We started and ran, and clapped our hands in joy of this sudden surprise. We found the main Tuolumne coming down at a right angle, with this side fall, and two joining together made a very imposing stream. We were puzzled on first observing the stream. It seemed impossible that there could be such a body of water coming from these falls, which had their head in Mount Hoffman and the summit snows. It was only after going up the foot of the last fall that we found the main Tuolumne coming down and alongside of a perpendicular wall, from which descended this side fall. After a little time spent in reconnoitering, we hastened back to the rest, for Muir and I had determined to camp there. That afternoon we camped by the side of the lower fall, just far enough away to be out of the reach of spray. One of the singular things I noticed about these falls was the sound. You could hear almost every musical instrument, but the dominant idea was as of a grand march played by one hundred thousand bands, all in perfect accord, and over all was as of the cries of men and women and children, advancing and retiring, and still coming nearer and nearer, until you were worked up to a painful tension of expectation. I have started often and often when sitting sketching, thinking I heard Indians talking near me.

The next morning I had a rather narrow escape. I went after some water for cooking, and I had to scramble along with bare hands and feet on the rocks, which slanted down to the river. I got up too high and where the slant was too sudden, I began to slide down slowly toward the river where, if I had got, it would have been the last of me. I was half asleep and dreadfully tired, but my sleepiness and tiredness vanished in the twinkling of an eye, when I suddenly discovered myself slipping involuntarily. I drew my hands up and dug them convulsively, and happened to strike a piece of crystallized quartz that was sticking up from the body of the solid rock. It struck me in the fleshy part of the hand and held me there until I gradually worked my way back to level rock.

The same morning we climbed to the base of the second fall, and built a bridge of logs over the stream where narrowed by the waters. In places it would be quite wide and flowing shallow over the bare granite. In other places it had worn a deep channel for itself. Over one of these narrow places we built our bridge and crossed with a rope round our bodies, for fear of tumbling in. We dragged our way over rocks and chaparral all day and camped at night, after crossing the river on an immense tree which had fallen across. The tracks of bear were very plentiful, and in fact had been all along from our first camping place. The next day by the side of the river and at night we were treated to a rain-storm, but at last we reached the last camping place on our up trip. The next day we started up the river. The river at this point came over inclined rocks, surging and tearing its way in eddies and swirls. Sometimes it would strike an immense boulder and throw itself up fifty to a hundred feet, in a mass of shreds and spray, every conceivable shape and form—cloud shapes, lace forms. [Our course] gradually getting steeper and steeper and more slippery, we took off our shoes and stockings, and, clinging to the bare walls of ice-polished granite, wishing for Spaulding's glue, we climbed slowly backward up the incline to another bench. The Tuolumne has its rise in a glacier on the flank of Mount Lyell, and, with other streams, passes through the Tuolumne Meadows for twenty-five miles, and then, in six jumps, cascades, falls and glides, into the Tuolumne Canyon. We were now at the top of the second fall. Muir wanted to make some measurements, and so we went along to the top. We hastened down to where we had left our provisions, hungry and tired. We stopped for two days.

At last we made tracks for our last camping place, where we had left provisions. We got back to camp, and found all the provisions which we had left eaten by the bears. Their tracks were thick all around, and they had followed us along from the first camp. However, we never caught a glimpse of them, for which I was very thankful. From camp to camp we plodded, making our home trip in three days, what had taken seven in going. The last day was the worst—the getting up from the bottom of the canyon to the top. I had left the rest and started ahead, half dead with hunger and fatigue—for the last three days we had been living on a short allowance of cracked wheat—and I was making for the flesh-pots on the top of the canyon, where we expected to find the packer with horses and provisions from Yosemite. I had got near to the top of a long snow-slide after a long tramp, and fondly fancied that I was close on the camp we had left twelve days before, when, horrible to tell, another set of cliffs broke on my view as I lifted my eyes to gloat on the short space I had to travel to the top, and I crossed some moraine and on to another snow-bank, which I proceeded to climb tearfully and regretfully. I was getting cold and the sun had gone down as I neared the top of this last snow-slide, when suddenly my foot slid out from under me, my pack gave a twirl, and I was on my back and sliding down that bank at the rate of one hundred miles an hour. It took my breath away when I found myself bounced feet foremost against a big boulder. I enjoyed myself a little while before I got up on my feet, and took a cool survey of my surroundings. I got to the top delirious with hunger and fatigue, but it was a welcome sound when in answer to my shouts I heard the return shouts of the packer who had arrived from Yosemite with horses and provisions. The packer had bought a sheep of some shepherds who had a flock of two or three thousand feeding among the meadows between the summit and Yosemite, and I had a right royal feast of mutton-chops and sugar, having been without the latter for twelve days. We returned without further adventure and with a marvelous experience fixed in our memories.

[1] Optical Character Read from Harlow, Ann. Ed., Supplement, William Keith: The Saint Mary's College Collection. Hearst Art Gallery, Saint Mary's College of California. 1994

[2] The Wasp (San Francisco), February 9, 1907, p. 92 (reprinted from Boston Daily Advertiser, 1874, exact date unknown).

[3] The Wasp (San Francisco), March 2, 1907, p. 140 (reprinted from Boston Daily Advertiser, 1874, exact date unknown).